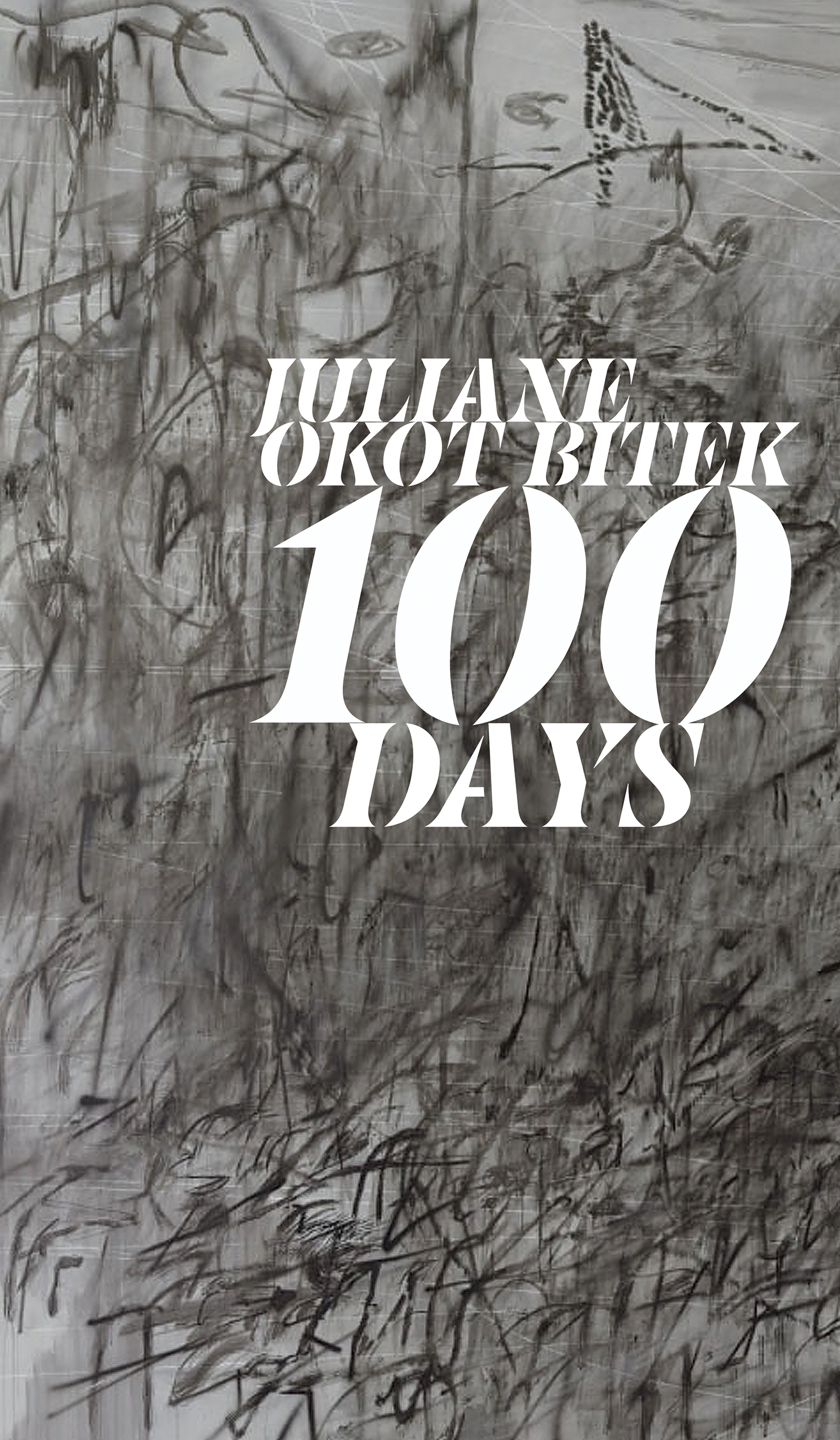

The poet, writer and scholar, Juliane Okot Bitek mines history for meaning and revelation. Her own, as she is the daughter of seminal poet, Okot p'Bitek and East Africa's, in particular the Rwandan genocide. Her first published collection is 100 Days and here she discusses its weighty uncomfortable truths, the role of the poet and the emotional process of retelling history.

this is what happens when you start counting

days in hundreds from a date that never was

Day 77

Juliane, thank you for sharing your work with me. 100 Days is a moving countdown that pays tribute to and records the horrific Rwandan genocide. In your author note, you write that these poems began as collaboration with Wangechi Mutu, a Kenyan-American artist. You mention meeting Yolande Mukagasana, a Rwandan poet, whose voice filtered into this project. For people who are unfamiliar with this collection, could you explain more about how it began and found its way to becoming a book?

Some of us fell between words

& some of us onto the sharp edges

at the end of sentences

Day 23

JULIANE: I wrote the poems in a public collaboration along with Wangechi Mutu who posted photographs for a hundred days beginning on April 6, 2014. As soon as I saw the first photo on Facebook, I knew immediately what Wangechi was attempting to do and asked her if I could write a poem along with her photos. So from the beginning of April through to July, Wangechi and I posted everyday on social media. It was a loose collaboration. I didn’t wait for her posts and she didn’t wait for mine, but more often than not the photo and the poem came together powerfully.

But to be true, 100 Days was working itself for many years before I ever imagined I’d ever write it. The woman I dedicate the book to, Yolanda Mukagasana, was an invited poet to the 18th International Poetry Festival in Medellin, Colombia, along with me and several other local and international poets. I will never forget her telling of surviving the genocide and losing her family in July of 2008. Her words seeped through into Day 97 of 100 Days.

The poet told us about her brother

Who spoke of a dream in which everybody would die

They would kill everybody

Except me she said

except me

Day 97

You write, "How could it be that the only Africans to think about the genocide would be from Rwanda? And yet the genocide was ours, too; it was a crime against us, East Africans and Africans. It was a crime, as all of them are, against all humanity." This seems a key point; that violence spills past borders and spreads culpability. Can you talk more about your use of words in this context and your feelings of responsibility as an artist?

There is a slope that leads

from these days of fiction

into nightmares that are real

Day 35

JULIANE: The role of an artist has long been debated between those for whom art exists for its own sake and others for whom art must be political. To comment on that quote, I have to collect all my sensibilities, not just my artistic self. I wrote 100 Days as an African woman and Canadian national who lives continents away from home and so I was thinking about proximity, solidarity, and witnessing. I wrote as a scholar who has been thinking and writing about how a violent political history shapes us.

That said, I come from a tradition of people who believe that the role of the poet/singer is that of a critic and a historian. My father wrote in Artist, the Ruler and The Horn of My Love that the poet is unafraid to say/write/sing what others would baulk from. This takes courage and leadership from the poet but the work of the art is to challenge people to think about what is going on.

However, to do this effectively, the artist must think about aesthetics — it must be attractive, it must be memorable, it must be innovative. The craft creates the artist. Beauty therefore is not idle; beauty cannot be beautiful just to be beautiful. It demands our attention and so it must contain a message or move us to thinking, talking and perhaps to action. Art, beyond the artist, is created in the moment of interaction and so beauty works behind the apparent aesthetic. Various recent and past histories across the world support the idea of the artist as dangerous precisely because he or she will challenge the status quo with their work. I was born in exile because of my father’s poetry so should know something about the power of art.

When the 1994 Rwandan genocide took place, I was a young woman, a new mother and I felt lost in my inability to express my position on it. At the same time, the violence that was being perpetrated in my homeland in northern Uganda was numbing and seemed endless. It was not enough to read the headlines (shout out to Peter Kagayi’s The Headlines that Morning) about what was going on in Bosnia and Darfur but it seemed like it was all I could do. It took me twenty years to find the words for 100 Days. I wrote as a woman who is from East Africa, who identifies as African and is a scholar of the violent history of that region. Often enough, those who could've told us first-hand about what happened cannot speak — they’re dead, they’re numb, they do not want to re-inscribe the world with the telling of the nightmares (as Indian anthropologist Veena Das writes). The artist then takes on the work of expressing the dread, documenting horror and locating the thread of life that we must hang on to.

We stumbled into the river

Where words go to die

& where words come from

Day 7

Your poems made me feel as if I was reading across stitches, these tiny bridges over wounds. What did the process of writing over a hundred days do to you? In that, was it healing, exhausting or deepen the hurt?

JULIANE: Writing 100 Days was not healing. It couldn’t be. It was thoroughly exhausting and when I was done I felt like I was one huge vacuous container. I was empty, devoid of any semblance of intelligence, used up. Dramatic, yes, but that is what it felt like. But I was humbled and happy to have been carried along the stamina required to get it done. I was thankful for the solidarity across the North American continent, knowing that Wangechi was doing the same work in the east coast as I was on the west coast. And we were buoyed along by many cheerleaders on social media as well as real life friends and family.

Stories in stories

Stories stoking stories

Stories stalking stories

Stories in circles & circles

Those stories haven't yet killed me

Day 9

You are writer with a wide range, including award-winning short stories and a plethora of essays. How did your childhood feed into the writer you are today?

JULIANE: I suppose like many people who write in the present, there is a historical love of books and often presence of books in the home. I loved to read as a child and my parents encouraged me to write.

That my loss was inevitable

That my loss was coming

That my heartbreak was written in the stars

& in historical documents

& even in the oral tales

Day 43

Where do you see your writing and work stretching towards in the future?

JULIANE: To tell the truth, I have no crystal ball and I don’t know how writing stretches but I’m always searching for a good story to read, or waiting for a good one to write.

we have run out of days

Day 1

On Juliane’s Bedside

I’ve got books all over my house, except for the kitchen. Madeleine Thien’s recently Man Booker Prize-nominated Do Not Say We Have Nothing is the only fiction on my bedside table but I’m saving it as a treat for when I accomplish a couple of things on an on-going list.

I’m re-reading James Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts, Politics and the Military in Uganda 1890-1985 by Amii Omara Otunnu and Okot p’Bitek’s Horn of My Love.

The three books that blew my mind in the last year are: Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route by Saidiya Hartman, Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine and Zong! by M. NourbeSe Phillip. Hartman, Rankine and Phillip: three writers who take on the impact of history on the intimate and social present. What does it mean to be alive today in the presence of such hard histories? Those are fantastic readings on that question.