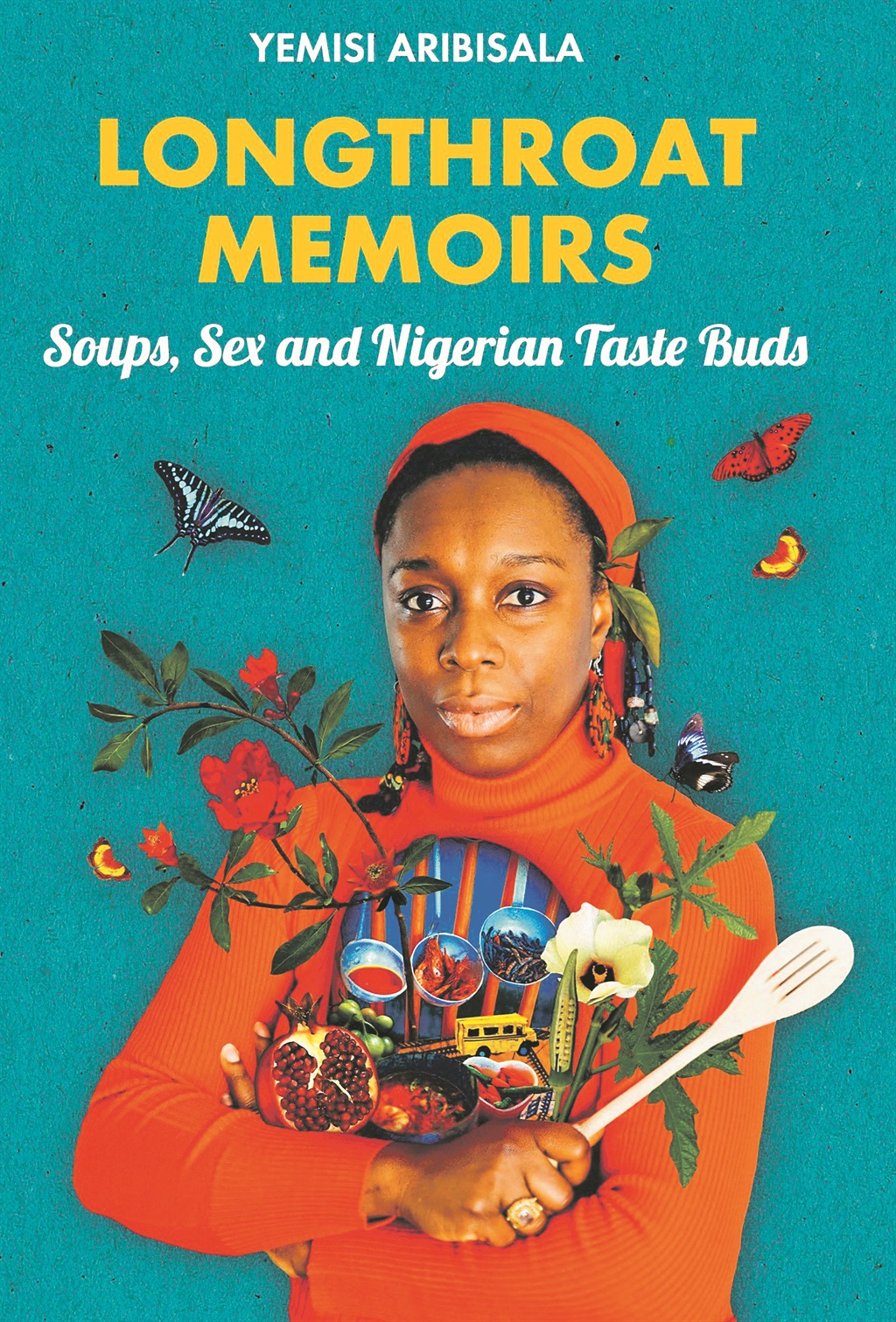

Lauren Smith interviewed our #WriterWednesday, outspoken essayist and food writer Yemisi Aribisala. They delved into what really makes an essay sing, pleasing the palate and Yemisi's new deliciously-written book Longthroat Memoirs: Soup, Sex and Nigerian Tastebuds.

What, for you, is the key to good food writing or to writing essays?

YEMISI: Investing one’s own disadvantage in words: Opening an artery onto the page, that kind of thing, apart from a love for the theme being written on.

There is a biblical king who sees that the battle he is fighting is about to be lost. He takes his oldest son, who is to succeed him, and offers him as a burnt offering on the walls of the city. The battle turns immediately in his favour. The words used are, ‘A great wrath was unleashed against the other side.’ This passive construction is surely referring to something other than the force used by the people fighting the battle. There are some levels of enchantment, some sacrifices that get a primal response – what happens when a child who is not yours, who you don’t know, falls down in the park and your heart breaks and you jump to your feet? It isn’t your business but you are part of something transcendent, and the child might as well be yours. There are many things that happen in the human being that bypass the brain.

I think that some essayists write what is in their heads and they write it for the intellectual prestige of putting down the words. Then they go on to expect the reader to care deeply and the reader doesn’t. If one wants to be a good essayist, one needs to connect and do it at the level of the gut, infiltrate the blood–brain barrier and lose prestige or the footing of pride. Or shall I say, you have to give something of value away to gain the investment of the reader’s time and attention. The subject matter has to mean something more than the mundane to the writer, and the exposé has to ultimately be on vulnerability. I don’t even have to say that the writer has got to write with integrity.

When talking about food and the sensuality of food, you would naturally discuss taste, smell, colour, presentation, etc. However, you also talk about the pleasure of saying words like ‘akara’ or ‘ila cocao’ and how you teared up at the words ‘soft custard of slowly scrambled eggs’. Does sound and language play an important role in the way you experience and enjoy food?

YEMISI: I have a theory about a woman’s chief erogenous zone. I think we can map it somewhere in the brain. I’m speaking from experience. My brain responds to spoken words with their impregnations of nuance and layers, much more so than the urgency of visual presentations. Words move more deliberately than visual images. I can isolate them and really think about them. I can stop them and start them again from retentive memory. The imagery that heard-words craft is more indelible. They are scattershot, full of possibilities, as opposed to the incarceration of visuals.

It probably works differently for other people. I find television, with its combination of sound and fast images, distracting and disquieting; a precursor to pounding headaches. I can’t turn around and watch at the same time. Audiobooks are soothing and freeing, and my ears and brain work better when my legs are in motion. The men that I have fallen passionately for were able to wield words. Spoken words. They were able to convey great passion in speaking, and I mean sincere feeling, not bullshit or charm.

Sound and language have everything to do with how I experience everything. Strangers are more powerfully observed in their words than in their appearance. I can hear all the layers when I can only see what they want me to see. With my back turned, I can sense a lie being spoken. Even feeling in languages that I don’t know makes a strong impression on me. Words applied to food and describing food – of course something explosive happens.

‘My imagination is always ahead of real life’, you’ve said, and Longthroat Memoirs has many examples of the ways in which your personality and proclivities seem to clash with things like meticulous measurements or the stodge of tradition. How have Nigerian readers responded to your radical creativity with local cuisine?

YEMISI: I don’t think that it is radical at all. The corollary is that many people are applying creativity to the preparation of their food every day. They probably don’t feel a need to talk about it, or write about it. I’ve said before that we don’t have a Nigerian culture of cooking and monologuing. It is coming along now with social media and Nigerian food celebrities. Readers of Longthroat Memoirs understand that I am not a methodical cook so there is a lot of forgiveness as regards to my recipes. Some pointed out mistakes as well. I think in the end readers are more comfortable with my imperfections than with a not very convincing expertise on Nigerian food.

You certainly never seem to shy away from topics or ideas that seem geared to unsettle readers. Longthroat delves into the eating of dog, ram penis, and animals on the verge of extinction. You’ve declared, in ‘Sister Outsider’, that you’re not a feminist and never will be, because it portrays itself as a kind of thuggish demand for conformity. You’ve argued that sexual repression is as legitimate as freedom. All your writing is full of strong opinions, brazen descriptions and merciless anecdotes. Where do you get this incredible energy from? Is it what inspires you to write?

YEMISI: I come from a society where the default is conformity. I don’t know how to conform and I find myself putting question marks against everything. If I cannot write ‘Sister Outsider’ in the way that I have written it as a feminist, then isn’t it, in the end, a disservice to my journey and my person to be one?

‘Sister Outsider’ opens with the line, "I have never had intrinsic fuckability." I find that your self-deprecation is so bold it comes across as strength and confidence. You often embrace the negation of what is popular and comfortable. Have you found this a useful way of thinking and writing about personal or contentious topics?

YEMISI: Not so much ‘useful’ as ‘unavoidable’. I am attempting to be true to myself. To be as truthful about myself as I can be without being self-indulgent or acquiring a taste for self-exposure. That taste going by Facebook entries is unquenchable. There is a need to speak on something and I don’t agree with the status quo. The self-deprecation probably comes from not fitting in no matter how hard I try.

‘Sister Outsider’ was written with painful awareness of not being the ideal Nigerian woman. Someone I once worked for asked me "Do you think you’ll ever be able to get it?!" He was talking about some technical task that he had spent a long time showing me how to do. I did get it … eventually, but the words remind me of my failure at getting the finer points of being Nigerian and woman and beautiful and accepted. I have sisters who managed this without even trying. What better way to spend one’s time in the country of fringe dwellers than capitalising on one’s failures? Why wallow in failure? If you can’t beat them, or join them, then you write about them. Yes, it does end up as a kind of power and advantageous positioning in standing out from the crowd because most people don’t want fringe-dweller strength. They want the comfort of close circles and cliques and sisterhoods and other such embraces that require allegiance. The allegiance must be paid for, but if you are an outsider you have nothing to lose, no currency that is accepted. You are cold already and rejection is familiar. It is what it is.

In your essay ‘Giving It All Away in English’, you describe English in the Nigerian context as "an antibiotic, sterile, necessary, but aloof. It is not the blood flowing through our veins. It does not fire up like language on the lips of those pouting neurotic nymphets in French films with English subtitles. It will never make Fidel Castro’s fists pump up and down, or rouse revolutions."

How do you feel, then, writing in this ‘tree-of-good-and-evil’ language that was enforced through colonial rule?

YEMISI: I feel grateful for the power to connect not only with Nigerians but many parts of the world without having to arduously and ineffectively translate what I have in my head. I feel grateful for the education that provided this ability and opportunity. My sympathies and empathy are with the people who find it difficult to adequately translate their thoughts into English or another language even in a basic capacity. There is nothing any of us can do about the fact that the world is shrinking so we need to learn how to speak more languages, not fewer. I feel sympathy for those who must use English or attempt to do so every day in order to connect with other people in institutions, to get money out of the bank, to navigate their way to their flights, to earn a grain of respect in a restaurant. In Nigeria, we have given ourselves no other option than the institutional use of the English language. We haven’t, in addition, provided the necessity and the resources of mastering the use of multiple languages. And that opportunity is so pertinent.

Then we have descended one step down the rung of decency by discriminating against those who don’t speak it well or who speak it with a Nigerian accent. We also elevate those who speak with an American accent no matter how idiotic they sound in their adoption of nasal manipulations and pretentiousness. It is painful to watch a grown man who had an inconsistent education in English, who is, by the way, beautifully articulate in expressions in an indigenous Nigerian language, who is a good human being, who is vocationally successful, smart and competent, being prematurely judged and disdained because he has made one or two grammatical mistakes.

‘Giving It All Away in English’ was one of the first articles that I wrote for Farafina Magazine because I had very strong feelings about the failure of our educational system in taking up the opportunity of multilingualism and instead infusing the learning and use of English language ‘in Nigeria’ with discrimination and class pretentiousness and condescension.

On the other hand, ‘Giving It All Away in English’ also praises the idiosyncrasies of Nigerian ways of speaking English. In what ways do you consider your own writing to be particularly Nigerian?

YEMISI: Thematically, they are Nigerian. I am writing all the time on being Nigerian and living in Nigeria but I have been accused of being stylistically un-Nigerian. My direct address of taboo objects, subjects and descriptions of people are supposedly un-Nigerian.

You and your son have a list of food intolerances so long that you can’t eat out and you descended into the depths of ‘Satan Street’ to find an organic local pot that wouldn’t release chemicals into your food. However, food intolerances are often scorned as mere fussiness or silly dietary fads. Does this attitude create much of a problem for you as a food writer? Or has it inspired you to cook because you can’t rely on others to cook for you?

YEMISI: The important thing is what works in reality. I think we can establish that the human body rarely responds to one-size-fits-all interventions in curing disease or even in maintaining health and balance. Popular impressions and conclusions about food are only really good for creating a market to sell a product to as many people as possible. The gut is such a private jurisdiction that an attitude or a proposal made regarding eating in real life never really translates successfully to the dietary habits of a wide surface area of humanity, in the very same way that impressions on taste do not either.

I see the scorn of dietary proposals as a backlash to the application of one conclusion on food to large tracts of people under the heading of ‘Good For You’. Both standpoints of general moral proposals and general rejections are cynical in their application. When you start to hear how wonderful coconut oil is for everything, question it and apply wisdom to its wholesale adoption for yourself. Also, when you start to hear how coconut oil is saturated fat and will kill you with heart disease, question it and do your research. A lot of the information on food out there is sponsored by markets and supported by trends, in the same way that the words written on the back of food packaging is more concerned about your buying the product than your health status. The lesson in it all is to have your own mind and listen to your own body and do your own research. Something else that marketing food has successfully disconnected from eating is the fact that we are meant to be providing resources for our bodies to function optimally and heal. Eating food should be pleasurable but we have to be pleasured and sustained too.

My own reactions to information on food differ depending on what I have found out in putting the food in my own mouth. Or based on how those who I cook for respond to the food prepared. For example, to start, in order to heal damage to our guts from wherever the damage emanated, we had to declare a no-gluten diet. To aid healing, we had to include many fermented foods and drinks and probiotics and to ingest as few additives to food as possible. After a few years, a little gluten was digestible but the additives are still a problem. Many of them are not food. They are metals or chemicals or colourings or wood shavings, or unidentifiable concoctions put in the food to extend the life or enhance the appearance of the food.

So now you understand from the ramble that the gluten in small quantities is no longer the problem but the things being commercially added to food. How anyone can argue with this premise, not only because it is personal and we as a family are not advocating it for everyone in our catchment area … and more importantly because we have tested it and found that it works for us. Paramountly, in the discussion there are pointers to items that are not in fact food … how anyone can argue with this is beyond understanding.

If a child breaks out in a rash every time he is given a biscuit, how can we conclude that not giving him the biscuit is a silly dietary fad? I think the other person can say for themselves, I can eat every kind of biscuit that I meet. Or, Eating biscuits doesn’t cause a reaction in my own body, but when the Epi-pen is being inserted into the thigh of someone choking on a peanut in the airplane seat next to me, the rational thing to do isn’t to conclude that the person gasping for air as his trachea is closing up is being fussy. What is obviously happening is that the person is fighting for her life.

Therefore, attitude hardly counts at all when we are attempting to determine what foods nourish the body. A lot of intolerances and allergies as they concern individual bodies are life and death issues and toxicology issues. Many of these issues fall outside the domain and patience of the orthodox practice of medicine. The institutionalised curing of disease is mostly a one-size-fits-all method that attempts to apply general medicine to individual bodies. ‘Generally’, this works, but when we have the many ‘one-offs’ of painkillers killing people and not pain because there is an allergic reaction to the content of the medicine, then functional medicine becomes a necessity. There is nothing smart about scoffing at that. I cannot have a problem with bringing awareness to these kinds of facts as a food writer; rather, it is my role to highlight the crucial attention to individuality in the decisions concerning our food. It is important not to just take anyone’s word over the evidence of ones’ own experience.

You’re currently based in Cape Town. How has living here – and in SA in general – added to your thoughts and experiences of food, feminism or language?

YEMISI: We’ve been predictable and made fast friends with the Nigerian woman in Lwandle who sells yams and okro and ugwu and banga in a huge tin, and palm oil in recycled water bottles. The tripe isn’t fantastic but it’ll do. It couldn’t have happened any other way. The fruits and vegetables in the Western Cape are beyond gorgeous. Organic is even better. I have never found such delicious broccoli anywhere. Nor have I, with such confidence, eaten red sweet potatoes with their skin on. It was the Western Cape that gave me the secrets of making my own coffee from scratch. I love Real Food Co., the organic grocers on Fagan Street, a short drive from us. I’ve developed all kinds of unaffordable addictions to stuffed olives made in small batches, R40 bottles of Kombucha, artisan chocolate and the most amazing dried figs. Oh, South African lamb! Just perfect! I will gladly eat spoons of local honey for dessert. That craving for honey has only developed here in the Western Cape.

Like in rural parts of Nigeria, there is a residual pride in producing food slowly, with concentration and integrity, and the best part of being here has been discovering people who just want to do that and will do everything they can to keep the quality of their food a priority. There are many wonderful alternative cures I have discovered related to food. For example, if you are suffering from hayfever, eat the honey from the area where your symptoms are most dramatic, or just from where you live, and you will be cured.

The interesting thing about feminism and my experience in the Western Cape is that the Afrikaner women seem to be in charge. They are beautiful, big-boned, with hair to die for. The men are quite shabby and subdued next to them and do as they are told. It makes me wonder if it makes feminism ever so slightly insignificant. Well, at least in the Afrikaner community. I understand I might be reading the dynamics all wrong but it is a very enjoyable misunderstanding if it is so.

Yemisi Aribisala is a writer and a lover of good food. She has written about Nigerian cuisine for over seven years for 234Next, Chimurenga Chronic and on her blog. Her essays on food are a lens through which the complex entity of Nigeria is observed. Yemisi has written essays on various topics including feminism, Nigerian Christianity and identity.

Interview by Lauren Smith a.k.a. @Violin_InA_Void